From the age of eight, Tran To Nga resisted the French and US occupations of Vietnam as a messenger, war reporter, and officer for the National Liberation Front. Then, during the Vietnam War, she was sprayed with a “poisonous powder” that caused her baby to die.

Now she’s bringing the war home with a lawsuit in a French court that accuses the toxic chemical’s US-based manufacturers of poisoning her and her family. (Hearings on the suit began this January in Paris.) Directors Kate Taverna and Alan Adelson’s globetrotting, award-winning documentary The People vs. Agent Orange follows Tran and a group of international activists’ quest for justice in the decades-long aftermath of chemical warfare.

In an era of divisiveness, the film transcends the race and labor-versus-conservationist divide. It shows how the logging industry and chemical companies have undue influence over politicians and the Pentagon. Ordinary people — Vietnamese, Oregonian, those following orders on the job or in the military — suffer alike. The Empire’s extraction and war machine profiteer — humanity, wildlife, the planet be damned.

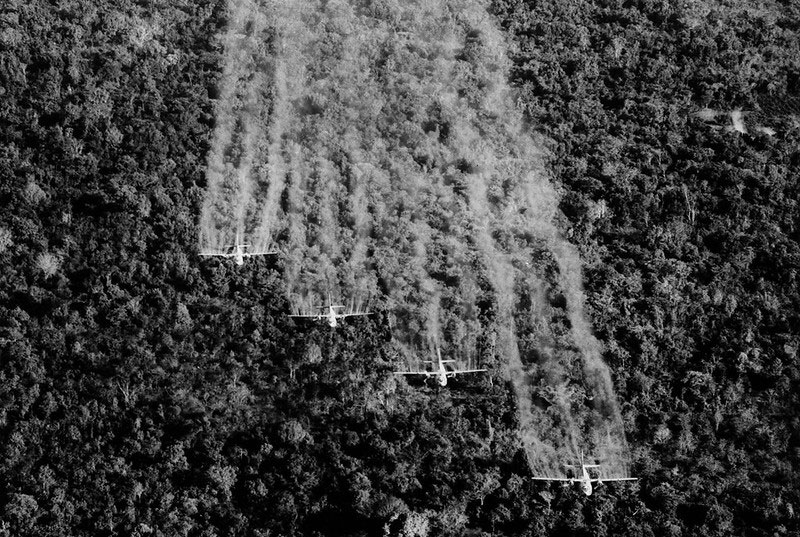

During the Vietnam War, about 5 million Vietnamese were exposed to an herbicide and defoliant known as Agent Orange. The US military dropped 20 million gallons of it to deprive Vietnamese guerrillas of the jungle foliage camouflaging them. Operation Ranch Hand, as this assault was called, was “the most destructive instance of chemical warfare in modern history,” declares David Zierler, author of The Invention of Ecocide: Agent Orange, Vietnam, and the Scientists Who Changed the Way We Think About the Environment.

But Agent Orange wasn’t used only in Vietnam. Although deploying the defoliant in that country ended by 1971, its use continued on the other side of the Pacific. Among other things, Agent Orange contains dioxin, which is a known carcinogen and also causes birth defects. The film’s most disturbing sequence depicts Tran at a Vietnamese hospital, visiting children born decades after the war still suffering deformities allegedly due to Agent Orange.

The film also follows Oregon environmentalist and Brower Lifetime Achievement Award Winner Carol Van Strum, author of a book on Agent Orange, A Bitter Fog, in her crusade against the herbicide. Pursuing a back-to-the-land lifestyle, Van Strum moved to rural Oregon in the 1970s, where she opposed the spraying of Agent Orange by the timber industry. Her activism allegedly led to corporate surveillance of her young family and threats of violence. Unthinkable tragedy strikes when her home is burned to the ground in 1978. Van Strum suspects it was deliberate arson, though investigators never determined the cause of the fire. The tragedy deepens her resolve to oppose the purveyors of poison.

Her work is supported by unlikely allies like helicopter technician Darryl Ivy, who participated in aerial spraying of Agent Orange in the Pacific Northwest until 2015, before realizing the possible environmental onslaught wreaked by the toxin. Using his cellphone, Ivy surreptitiously filmed how the herbicide was contaminating reservoirs in Oregon. And it includes Vietnam War veterans who were also victims of chemical exposure. Retired Air Force scientist James Clary, who documented the Pentagon’s dirty war, speaks out for the first time onscreen, declaring he’s angry his “own government does not want to help veterans suffering” from Agent Orange’s lingering effects.

Crusading authors, attorneys, and activists sought to hold manufacturers, including Dow and Monsanto, accountable in courts and at the polls. But as spraying continued in Oregon, tactics escalated from civil disobedience to violence. Helicopters were shot at and burned. Masked militants warned via graffiti: You spray you pay. You kill we kill. We shall strike again.

The documentary combines archival footage, news clips, home movies, and original material shot at international locations, including Vietnam, Paris, and Oregon. One vintage vignette transports viewers south of Hawai’i to the top-secret Johnston Atoll hellhole, where the US Department of Defense incinerated and buried large amounts of Agent Orange.

Directors Taverna and Adelson have made several nonfiction films together, including 1988’s anti-Nazi Lodz Ghetto. Adelson brings his investigative journalism background to bear on this well-crafted 86-minute documentary that ends on an active note, almost a call to action, as Vietnamese children and adults, deformed and disabled by dioxins, many in wheelchairs, stage a march against Agent Orange. The admirable Tran asserts that she’s “fighting for American victims too.”

We don’t have a paywall because, as a nonprofit publication, our mission is to inform, educate and inspire action to protect our living world. Which is why we rely on readers like you for support. If you believe in the work we do, please consider making a tax-deductible year-end donation to our Green Journalism Fund.

DonateGet four issues of the magazine at the discounted rate of $20.