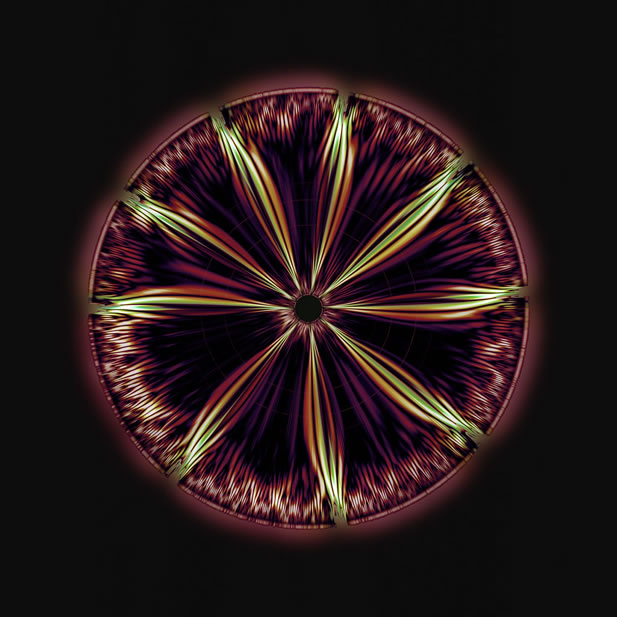

Mark FischerMade from the sound of a White-beaked dolphin, (Lagenorhynchus albirostris), recorded near Iceland.

Mark FischerMade from the sound of a White-beaked dolphin, (Lagenorhynchus albirostris), recorded near Iceland.

In 2001, while on vacation in Baja, Mexico, Mark Fischer trailed a “gorgeous” cachalot for three days in the Sea of Cortez as he accompanied a marine biologist who was recording the toothed whale’s song. The massive cetacean’s mysterious clicking and creaking calls got Fischer hooked on animal acoustics. But he soon found himself disenchanted by the spectrograms used to visually represent sound. He felt that the linear graphs didn’t quite capture the essence of the haunting sounds he’d heard. Nor did they give enough information about the nature of the vocalizations.

“Spectrograms are infinite; they have no beginning and no end,” he says. “They work well for visualizing musical scores or mechanical sounds, but there are very few sounds in nature that they can express in detail.”

So Fischer, a computer engineer by training, came up with a new visualization technique. He applied the mathematical theory of wavelets – oscillations that begin at zero, increase and then sink back to nil – to recordings of birds and marine mammals. Then, using a software program he wrote himself, he processed the wavelets into color-coded visual forms. The result: an explosion of neon-bright ripples and swirls that are mesmerizing representations of the natural world’s soundscapes.

The patterns, which Fischer often prints out as massive four by eight photos, are varied. Most of the forms are circular. They resemble delicate mandalas, or extreme close-ups of unusually colored irises, or starbursts. There are also rectangular patterns that are more reminiscent of traditional tapestries or, for the scientifically inclined, maybe DNA sequences.

The forms, Fischer says, reveal the wide range of frequencies and patterns within each animal call. He chose wavelets because they can pick out the subtle distinctions between different calls (Fischer calls them “dialects”) by the same species that may be inaudible to the untrained human ear. Wavelets, he says, can capture intricate detail without losing the bigger picture. Fischer describes his technique as a “kind of photographic process” that uses computing as a lens to create a visual structure for something that’s not normally seen. He calls the end product “the shape of the sound.”

Most of the sound recordings – which range from birdcalls in the forests of Costa Rica to the songs of white-beaked dolphins off the coast of Iceland – are gathered from wildlife researchers. Fischer hopes that some day scientists will be able to use wavelet-generated images to identify and track individual marine mammals. Several researchers, including scientists at Cornell University’s Bioacoustics Research Program and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, agree that his technique has potential as a scientific research tool.

But the images are also art for art’s sake. Fischer says they signify the continuance of life. They will, he hopes, inspire a greater appreciation of a wild world most of us rarely lend an ear to.

Mark Fischer’s sonic art is available at www.aguasonic.com.

The song of a Bee Hummingbird, (Mellisuga helenae), recorded in Cuba.

Made from the sound of a Humpback whale, (Megaptera novaeangliae), recorded near Cook Island by Nan Hauser.

Sounds of a white-beaked dolphin (Lagenorhynchus albirostris) recorded near Iceland.

Sounds of a Minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) recorded near Hawai‘i.

Sounds of a false killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens) recorded near the Azores Islands.

Sounds of an ‘Elepaio bird (Chasiempis sandwichensis sclateri) recorded on Kauai.

Sounds of an Atlantic Spotted dolphin, (Stenella frontalis), recorded near the Azores.

We don’t have a paywall because, as a nonprofit publication, our mission is to inform, educate and inspire action to protect our living world. Which is why we rely on readers like you for support. If you believe in the work we do, please consider making a tax-deductible year-end donation to our Green Journalism Fund.

DonateGet four issues of the magazine at the discounted rate of $20.