SEATED AROUND A SMALL, circular table on the second floor of a busy Istanbul café, three activists and I are heatedly discussing the intricacies of the Turkish government’s latest megaproject. The plan involves building an artificial channel on the western edge of Istanbul that would run parallel to the Bosphorus, a heavily trafficked natural strait that intersects this ancient city and divides the country between two continents, Europe and Asia.

“The matter isn’t siyasi (political) it is hayati (vital),” says one of the activists, pushing his index finger firmly against the table. The debate is spirited from the instant we meet, with each of the men trying adamantly to get his message across. “I would object to this project regardless of its mastermind — it could be my father’s plan and I wouldn’t care,” he adds, moving on to explain how the channel would cut through forests, marshes, farmlands, and several freshwater bodies, while his associates nod in agreement.

All three activists are associated with Ya Kanal Ya Istanbul (YKYI), a popular civilian initiative against the “ecological pillage” of the city. The name of the platform, which translates as “Either the Canal or Istanbul,” successfully conveys the widespread sentiment about the mega-infrastructure project that would form a second link between two inland seas — the Black Sea in the north and the Sea of Marmara to the south.

At the start of the interview, the activists somewhat jokingly raised concerns over my recording device, but then went on to refer to each other by old-fashioned, odd-sounding pseudonyms throughout our meeting. Their wariness is justified. Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is notorious for persecuting anyone who stands in the way of his political aspirations, including activists, journalists, or even ordinary citizens who dare express their dissenting views on social media. Speaking out against his initiatives can be risky. Besides, Erdoğan, who is a champion of large-scale construction projects despite their ecological toll, has repeatedly stated that he is determined to push this project through.

“Anyone who can put two and two together can understand how terrible this project is.”

Regardless of their reasonable worries, the activists have been courageously outspoken in their criticism of the Kanal Istanbul project, which the Turkish government, as of February, hoped to break ground on by the end of the year. The initial tender for a related construction was held late in March, despite a nationwide freeze on all other non-urgent matters due to the coronavirus pandemic.

One of the activists, an architect who decided to remain anonymous, says he joined the platform after reading parts of the environmental impact assessment (EIA) for the project published last December. “My immediate reaction to what I read was, Aman Allah’ım (Oh my God),” he says. The EIA, which the activists called a “promotion file,” is marred with inconsistencies and inaccuracies, he says. Indeed, the report made headlines for weeks after it was released, as thousands of citizens filed petitions of objection against it.

Anyone who can put two and two together can understand how terrible this project is, Fehmi Tığlı,one of the other activists, tells me. Unlike other well-known artificial channels such as the Suez or Panama canals, Kanal Istanbul has no ambition of shortening distances travelled by ships, he points out.

The stated motive of the channel is to divert traffic away from the narrow, tricky-to-navigate Bosphorus Strait — one of the world’s busiest waterways — by encouraging tankers, especially those carrying hazardous material such as oil and gas, to use the new passageway.

“The entire rationale of the project is problematic,” says Tığlı, who is also an architect. “If you consider the Bosphorus Strait to be dangerous, shouldn’t it follow that you build the second channel outside of the city?” he asks. “Instead, you are planning a narrower, more shallow channel with almost the same current velocity, and building a new city around it!”

ERDOGAN FIRST ANNOUNCED the plan for Kanal Istanbul back in 2011, as part of his re-election bid when he was still Turkey’s prime minister. The new canal, on the European side of the Bosphorus, would be completed by 2023, he announced at the time. The date marks the centenary celebrations of the Turkish Republic after the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the nation’s subsequent War of Independence.

The lasting influence of the country’s secular founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, has long provoked the envy of Erdoğan, who claims leadership of the country’s opposing, conservative camp. As the first politician to command as much power since Atatürk, Erdoğan’s rivalry with the man, whose given last name translates as “Father of all Turks,” adds to the significance of a 2023 completion date — it is the perfect opportunity for the seated president to showcase the extent of his own legacy.

“Turkey more than deserves to enter 2023 with such a crazy and magnificent project,” he said while making the announcement in 2011. “Istanbul will become a city with two seas passing through it.”

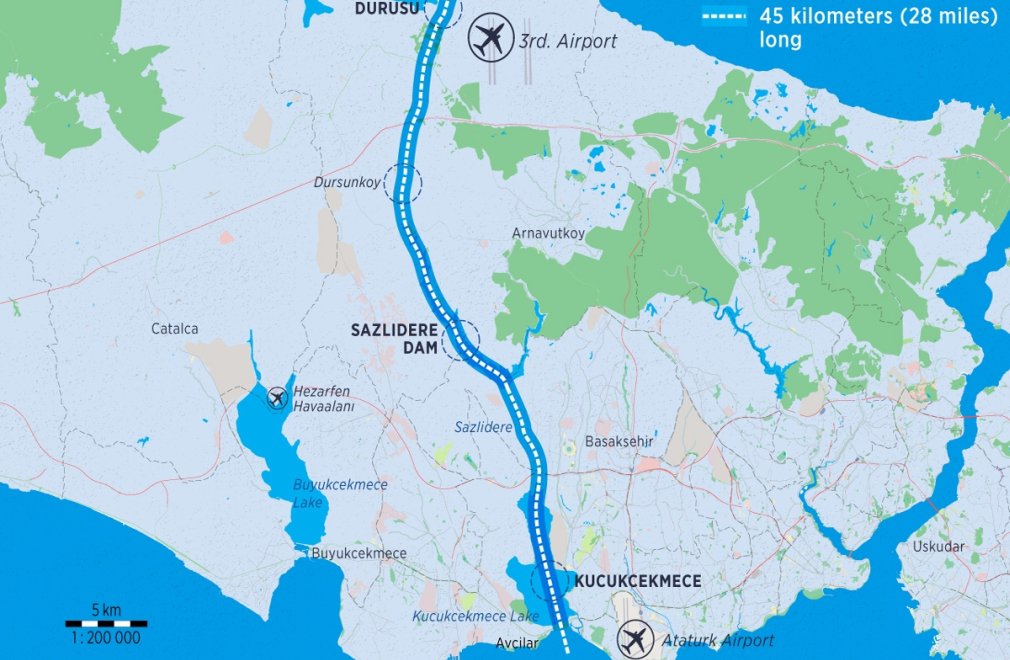

After mulling over several alternatives, the final route of the canal — which is part of three interlinked projects, including a massive new airport on the city’s outskirts and a third bridge across the Bosphorus — was announced in January 2018.

According to the final plan, the 28-mile channel will start at Küçükçekmece Lake, a natural lagoon on the Marmara Sea to the west of the Bosphorus, go north through Sazlıdere Dam (which supplies the European side of Istanbul and its suburbs with drinking water), and connect to the Black Sea farther up north. When finished, the canal will redraw the map of Istanbul, turning its western side — which includes the city’s historic center — into an island. The project is expected to cost anything between $10 and $20 billion.

By the time the route was announced, however, it was becoming increasingly apparent that the Turkish economy was on a downslide and the government was forced to freeze investments in large infrastructure projects, including this one. Still, by December last year, Erdoğan had again put the project back at the top of his domestic agenda, much to the consternation of many local environmentalists and urban planners.

Ships waiting in the Marmara Sea. With more than 43,000 vessels passing through the narrow Bosphorus every year, accidents are difficult to avoid. Additionally, traffic congestion often leaves ships sitting in queues off the strait for days on end. Photo by Hans Birger Nilsen.

The main purpose of the project is purportedly to reduce the risk posed by vessels carrying hazardous materials through the Bosphorus, which, due to its strategic location as part of the continental boundary between Europe and Asia, is one of the most crowded waterways in the world. The strait offers the only maritime passage from the Black Sea into the Sea of Marmara. It is also the only passageway connecting the Black Sea to the Aegean and Mediterranean seas, via the Dardanelles Strait that lies on southwest end of Marmara. (The two straits are collectively known as the Turkish Straits.)

With an average of 43,000 vessels passing through the narrow Bosphorus every year, more than two times the traffic of the Suez Canal, accidents like ship collisions, groundings, fires, and oil spills are difficult to avoid. Additionally, traffic congestion often leaves ships sitting in queues off the strait for days on end. Kanal Istanbul, which is expected to allow for 160 vessel transits a day, will divert most of this traffic from the Bosphorus, its proponents say. (Opponents of the project counter that shipping traffic is actually steadily declining since reaching its zenith in 2007 and that accidents have been declining ever since stricter safety measures were put in place in 2003.)

For the proponents of the project, a second advantage of the new channel is financial.

The new channel will be around 65 feet deep and its width will range from 902 feet to 3,280 feet (1 kilometer). Critics of the project point out that the new canal is relatively small: The narrowest point of the Bosphorus is 2,290 feet, only about 1,000 feet short of the widest point of the new channel. Nonetheless, the supporters of the project argue that Kanal Istanbul would be safer since it doesn’t have the sharp turns of the Bosphorus.

For the proponents of the project, a second advantage of the new channel is financial.

There are plans afoot to build several new neighborhoods along the canal’s route, and huge investments in residential and commercial real estate in those areas are expected. With construction on the canal set to start soon, land along the proposed route has already become highly sought-after. Additionally, official plans estimate an annual revenue of $1 billion via service fees from vessels passing through the new canal, though there is speculation that the figure could be as high as $8 billion.

There are concerns, however, that the government’s revenue-generation plan could be seen as a violation of the 1936 Montreux Convention, which governs the Turkish Straits. In keeping with the convention, Turkey charges a fixed fee for international commercial vessels passing through the straits based on the tonnage. By some estimates, the fee is, on average, more than 10 times lower than fees charged by other channels. Transit through the Suez Canal, for instance, costs around $465,000. While Turkey’s bid to increase its revenues is understandable, critics say ships would likely not want to pay drastically higher figures to pass through the canal when a cheaper alternative exists.

Montreux also governs the passage of military vessels, and guarantees free passage for naval ships of countries along the Black Sea, including Russia, except during wars. The safety of riparian states is further ensured through restrictions on the naval ships of all other countries, including from the United States. Within this context, opening up a second route to the Black Sea that would not be governed by the convention would be a risky gamble, say seasoned diplomats and legal experts.

The possibility of a diplomatic imbroglio is, however, hardly as unsettling to some as the prospect of the massive, irreversible harm the project will inflict upon the ecology of this old imperial city, the agricultural lands on its outskirts, local freshwater ecosystems, and the delicate balance that sustains the unique marine ecosystems of the Black and Marmara seas.

ON A QUIET SPING MORNING, I set out on the road to see the areas the canal would pass through for myself. I drove north towards Istanbul’s western suburbs, along the empty, smoothly paved highways freshly built for easy access to the city’s massive new airport that started partial operations last year.

The channel will begin west of Istanbul’s massive new airport, part of which is being built on some 1,500 acres of the Northern Forests — a vast, 600,000 acre-swath of natural forests stretching between the Black Sea and Marmara coasts that is commonly known as the city’s lungs. Photo by KpokeJlJla.

Lake Terkos is one of Istanbul’s seven important botanical areas. The new channel will not only harm this diverse ecosystem through rapid urbanization, it will also expose the lake to the risk of salinization. Photo by Selin Ugurtas.

Küçükçekmece Lake, the southernmost point of the channel, is a lagoon on the shore of the Sea of Marmara that supports a wetland of vital importance to many marine animals and birds. Photo by Ahmet Hikmet Turan.

The channel will begin to the west of this airport, part of which is being built on some 1,500 acres of the Northern Forests — a vast, 600,000 acre-swath of natural forests, rivers, lakes, wetlands, and coastal dunes stretching between the Black Sea and Marmara coasts on both the European and Asian sides of Istanbul. The Northern Forests are commonly known as the city’s lungs for the fresh, clean air they provide Istanbul. They also produce much of the city’s drinking water and are a carbon sink for Istanbul’s urban emissions. The airport, and another associated megaproject, which involved constructing a third bridge across the Bosphorus, have been destroying this vital lifeline. The canal is going to add to this destruction.

Despite the deserted roads, it took nearly an hour to reach the northernmost point of the proposed channel, the small fishing town of Karaburun. The canal will journey south from here, passing near Lake Terkos, through the Sazlıdere Dam and reservoir, and eventually to Küçükçekmece Lake, where it will pass by two ancient sites — the Yarımburgaz caves to the north of the lake that are recognized as one of the earliest known human settlements in Europe, and the Byzantine port town of Bathonea on the lake’s western banks, which dates back to the second century BCE.

A five-minute drive from Karaburun, Lake Terkos is one of Istanbul’s seven important botanical areas. According to WWF Turkey, the area surrounding the lake is home to 575 plant species, including 73 rare plants, 13 of which are endemic to Istanbul.

I’m fascinated to learn of Istanbul’s unusual biodiversity. The city is home to some 2,500 plant species, more than the number of flowering plant species found in entire countries like United Kingdom, Poland, or the Netherlands. Dr. Emine Akalın Urusak, a professor of pharmaceutical botany at Istanbul University, explains that this is a result of Istanbul’s geographical position at a transition zone between Europe and Asia, in between two seas, which has resulted in it having a diversity of soils and climates.

While every Turkish schoolchild memorizes a description of their country as “surrounded by waters,” Budak emphasizes that Turkey is not a water-rich country.

Lake Terkos, from which the city has been drawing water since the Roman times, is one of those rare areas within this ever-expanding metropolis that has managed to survive unharmed so far. It is also the largest freshwater resource on the city’s European side and, along with the Sazlıdere reservoir, it accounts for a quarter of Istanbul’s water supply. The construction of the channel will not only harm this diverse ecosystem through rapid urbanization, it will also expose the lake to the risk of salinization.

“The problem is, the new channel will run too close to the lake,” says Dr. Sevim Budak, a professor of urbanization and environmental studies at Istanbul University. “There might be an earthquake, there may be cracks [in] the isolation walls, especially whilst using explosives during construction, causing the channel’s salty waters to leak into the aquifers.”

The salinization would harm agricultural land in the area, as well.

While every Turkish schoolchild memorizes a description of their country as “surrounded by waters,” Budak emphasizes that Turkey is not a water-rich country. There can be no reasonable explanation for destroying existing freshwater resources, especially amidst the looming climate crisis that will further strain the city’s limited resources, she says.

The Sazlıdere Dam accounts for around 6 percent of Istanbul’s water supply. The main reservoir of the dam will be swallowed up by the canal. Photo by Seline Ugurtas.

The dam’s basin includes the Western Istanbul Heathlands, which supports a diverse ecosystem, including rare and globally endangered plant species such as the the eastern sowbread (Cyclamen coum). Photo by Uzi Yachin.

Midway through the designated route for Kanal Istanbul, the Sazlıdere Dam accounts for around 6 percent of Istanbul’s water supply. Just like Lake Terkos, the dam’s basin is another one of Istanbul’s important botanical areas. Known as the Western Istanbul Heathlands, it supports a diverse ecosystem on its calcareous soil, including rare and globally endangered plant species such as zarif kekik (Thymus aznavourii), the eastern sowbread (Cyclamen coum), and çokbaşlı köygöçüren’ or many-headed thistle (Cirsium polycephalum). The main reservoir of the dam will be swallowed up by the canal.

To the dismay of many scientists and activists, the loss of these habitats was downplayed by the project’s EIA, which, among other things, suggests that rare and endemic plants can be protected through preservation of their seeds, and the destruction of forests can be compensated for by planting more trees elsewhere. But as Dr. Pelin Giritlioğlu, professor of urbanization and environmental studies at Istanbul University, points out, forests are more than a collection of trees. “The soil, the fungi, the moss, the squirrels, the trees, they all come together to make the forest,” she explains. “Once you lose this ecosystem, you will not have a forest even if you plant ten times the number of trees.”

Those species that manage to survive the destruction wrought by the project will unfortunately experience further difficulties as the new channel will disconnect them from western lands, forcing them into isolation. Animals left on the eastern side of the channel will be confined to an island, unable to wander far in search of food or for reproduction. Scientists warn that this may result in population declines or eventual local disappearance of some species from these habitats. Since the animals will be forced to inbreed due to dropping populations, the emergence of genetic disorders is also a possibility.

My final stop for the day was the southernmost point of the channel — Küçükçekmece Lake, a lagoon on the shore of the Sea of Marmara that supports a wetland of vital importance to many marine animals and birds.

Thousands of white storks (Ciconia ciconia) and many pygmy cormorants (Phalacrocorax pygmaeus) frequent the lake during their migration season. The wetland is also an important wintering ground for the white-headed duck (Oxyura leucocephala), a globally endangered species, and it is one of the last remaining habitats of the lesser mole rat (Nannospalax leucodon).

The Küçükçekmece Lake is often described as an expendable resource as sewage from surrounding districts had been discharged into it for years, significantly damaging the aquatic habitat. But ecologists like Budak argue the lagoon should be preserved as a reserve from which water could be drawn in case of an emergency such as a war, or, quite prophetically, a pandemic.

Turkey is prone to earthquakes and the planned route of the canal traverses three active fault lines.

The town council of the Avcılar district, located on the western banks of the Küçükçekmece Lake, has opposed Kanal Istanbul since the start, and for good reason. In addition to the destruction of the nearby lake and the two neighboring cultural heritage sites, they say the project puts the district’s half-a-million residents at risk.

Turkey is prone to earthquakes and the planned route of the canal traverses three active fault lines. Construction work on the canal could increase the risk of earthquakes. Avcılar is built on a landfill that sits atop a first-degree seismic zone. Some 1,800 buildings in the district are at risk of collapse, and officials here have long been demanding urban redevelopment with earthquake-safe infrastructure, but that demand, says Turgay Halisçelik, Avcılar’s town council president, had fallen on deaf ears while the government announces one megaproject after another. Now, however, the Turkish people are beginning to pay some attention to their plight.

“Our slogan, ‘Budget for the earthquake, not for the channel’ is everywhere now,” he says.

The phrase has indeed hit a chord and became widely popular amidst the country’s ongoing economic slowdown. The town council’s now famous slogan seems to be evolving in tandem with the public’s changing concerns about these megaprojects and the ongoing pandemic. People can now be heard chanting: “Budget for corona, not for the channel” in a clear critique of how the government has been handling efforts to slow down the spread of the disease.

MOST SCIENTISTS AGREE that the most significant victim of Kanal Istanbul will be the Sea of Marmara, and that the devastation wreaked on the delicate ecological balance between it and the Black Sea will have wide repercussions across the region.

The Bosphorus Strait, which links the two seas, has an exceptionally rare, two-layered current system that Dr. Bayram Öztürk, a professor of marine biology at Istanbul University, calls “a wonder of fluid mechanics.” The two currents with widely different characteristics meet and mix in the Marmara.

.jpg/1024px-Blooms_in_the_Sea_of_Marmara_(18162220028).jpg)

The less salty, nutrient-rich waters of the otherwise landlocked Black Sea, which is 50 cm higher than Marmara, flow downstream through the Bosphorus as a 20-meter-deep upper current. In the meantime, the salty, oxygen-rich waters of the Mediterranean enter Marmara through the Dardanelles Strait and stay there for several years, before slowly moving up the Bosphorus as a lower current.

However, by the time the Mediterranean water reaches the Bosphorus as an undercurrent from the Marmara, it is already deprived of most of its oxygen because the microscopic biota in the upper current coming in from the Black Sea waters sink down and eat away the dissolved oxygen in Marmara’s waters. This is why Dr. Cemal Saydam, a professor of environmental engineering at Hacettepe University, describes the Sea of Marmara as an asthma patient, always short of oxygen. Opening up a new channel between the two seas would increase the flow of cellular organisms into the Marmara and would deplete it of even more oxygen and could eventually kill all life in it.

“Going through with this channel project would irreversibly choke the Sea of Marmara and leave it without oxygen,” Saydam says in an interview with the Turkish daily Cumhuriyet. Saydam and other ecologists say opening a second waterway connecting the two seas would be a death sentence for Marmara and its unique ecology.

According to WWF Turkey, Marmara’s plankton-rich waters are a “matchless pasture for fish larvae,” and hence a favorable feeding and spawning ground for various species. These include protected marine mammals such as the short-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus delphis) and the common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus), as well as species critical for the country’s fishing industry such as swordfish, mackerel, Atlantic bonito, bluefish, and anchovies. The industry, which caught and bred over 830 thousand tons of seafood in 2019, brought in $950 million in export revenue that year.

Marine biologist Öztürk warns the second channel would also expedite the influx of nonnative species into the Black Sea from Marmara as they move up the artificial channel in search of more nutrient-rich waters, a phenomenon called Lessepsian migration (in a nod to Ferdinand de Lesseps, the Frenchman who developed the Suez Canal). In fact, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1867 allowed species from the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea to cross into the Mediterranean and eventually reach as far north as the Black Sea.

For Turkey, the most notorious invaders were the sea walnuts (Mnemiopsis leidyi) that found their way into the Black Sea in the 1990s. Feeding heavily on zooplanktons, which many fish, including the region’s famous anchovies, depend upon, this stingless jellyfish-like animal caused dramatic declines in commercial fish populations. Öztürk warns that speeding up the migration of alien species could lead to similar incidents that would impact the Black Sea fishing industry, which provides some 70 percent of the country’s seafood supply.

UNFORTUNATELY, IF RECENT HISTORY is testament to anything, it is that public outcries are often overlooked, especially when democratic processes are undermined, as is the case in Turkey right now. Erdoğan has managed to realize all his megaprojects despite warnings from scientists, and he has so far been adamant about pushing this one through as well. As luck may have it, however, the struggle against the project has received a boost from Istanbul’s new mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu.

An up-and-coming member of the opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), İmamoğlu won the mayor’s seat in an unexpected victory against Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party last year and is leading a fierce battle against the canal. He emphasizes a lack of public consensus on Kanal Istanbul, which he says is an “outdated” attempt at construction-based growth that will “murder” the city and its environment.

The mayor’s support has energized activists, urban planners, and environmentalists who are accustomed to waging these battles alone.

Back at the city café in Istanbul, one of the Ya Kanal Ya Istanbul activists expressed hope that İmamoğlu’s team would take the lead in fighting the project. “This issue doesn’t only concern Istanbul,” he told me, while stressing the need for strong, coordinated opposition to the project. “It concerns the entire country. What’s more, it concerns Black Sea states, Aegean states, Mediterranean states.”

As Turkey gears up for a showdown between its longtime president and an emerging leader, it remains to be seen whether Erdoğan will succeed in pulling another fait accompli. It is evident, however, that the future of Istanbul’s vulnerable ecosystems, as well as the fate of the Black and Marmara seas, will be closely intertwined with the political future of the country.

We don’t have a paywall because, as a nonprofit publication, our mission is to inform, educate and inspire action to protect our living world. Which is why we rely on readers like you for support. If you believe in the work we do, please consider making a tax-deductible year-end donation to our Green Journalism Fund.

DonateGet four issues of the magazine at the discounted rate of $20.