When humans began domesticating wheat sometime around 7500 BC, they most often selected plants that boasted high and consistent yields. While this may have made sense for societies struggling with food shortages, it meant that many other important characteristics have been lost as grains went from wild to domesticated.

photo Andreas KrappweisScientist say it’s time to “re-wild” grains to make them more resilient to pests and drought.

photo Andreas KrappweisScientist say it’s time to “re-wild” grains to make them more resilient to pests and drought.

Now, some scientists say it’s time to “re-wild” food crops by inserting the lost genetic properties of ancient, edible plants back into today’s varieties of wheat and rice. A recent study in the journal Trends in Plant Science says that human selection has made food crops less resilient to stress. Rewilded crops could be more drought tolerant, better able to withstand extreme temperatures, more resistant to pests and diseases, and more efficient in accessing soil nutrients. “We estimate that all crops would benefit from re-wilding,” Michael Broberg Palmgren, a scientist at the University of Copenhagen and one of the study’s authors, told Reuters.

After years of bitter political wrangling, the European Union appears to have reached a compromise on genetically engineered crops. In January, the EU Parliament approved new legislation to allow member states to decide for themselves whether to restrict the cultivation of GE crops within their own territories.

The new rule will allow member states to ban transgenic crops even if the crop has already been cleared at the EU level. Somewhat ironically, this new law is likely to lead to approval of more GE crops. Since member-states now have the assurance they can ban a given crop if they like, EU officials are expected to green-light several GE crops that have been stuck in limbo for years.

The legislation, informally agreed to in December, was originally introduced in 2010 but was deadlocked for years due to disagreement between pro-GMO states (like Britain and Poland) and anti-GMO states (like France). “This agreement will ensure more flexibility for member states who wish to restrict the cultivation of the GMOs in their territory,” said Frédérique Ries, a Belgian politician and EU Parliament member who steered the legislation through the EU’s governing body. “It will, moreover, signpost a debate which is far from over between pro- and anti-GMO positions.”

Critics say the compromise looks good at the headline level, but in practice it will allow GE foods to enter the EU via a back door. “It is a bad measure because the EU will become a patchwork of GMO regimes when what we need is a common approach,” parliament member Rebecca Harms, a Green Party member, told the science news website Phys.org.

The biotech industry is also unhappy with the new law. Industry association EuropaBio says the legislation will hurt innovation because it allows member states to challenge GMOs “on non-scientific grounds.”

The plant scientists suggest using biotechnology to re-insert wild genes into domesticated plants. Palmgren and his colleagues hope that would be less controversial than other genetic modifications since it wouldn’t involve any transfer of genes among unrelated organisms.

While scientists are uncertain to what degree rewilding would boost grain harvests, they say that reintroducing ancient genetic material would help address challenges like climate change and soil degradation.

Beavers, perhaps best known for building dams, were once nearly annihilated by the fur trade of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. But these semi-aquatic rodents have made a comeback. Today, scientists estimate that there are more than 10 million beavers worldwide, damming rivers and streams to their hearts’ content.

That’s great. But here’s the catch: The low-oxygen ponds beavers create generate methane, which is released into the atmosphere. Researchers at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada estimate that beavers have created roughly 42,000 square kilometers of ponds globally. Based on estimates of pond area and beaver populations, this means beavers are responsible for roughly 800 million kilograms of methane emissions every year. That is 200 times higher than beaver-related emissions were a century ago.

Still, we can’t place the blame for global warming on the backs of beavers. Beaver ponds generate just 15 percent of the methane emissions produced by cud-chewing livestock like cows, sheep, and goats, and humans are ultimately responsible for 60 percent of all global methane emissions.

When it comes to shopping, some monkeys are smarter than humans: They don’t get taken in by expensive brands.

Past research has shown that, if given a choice, people tend to pick the more expensive options. A 2008 study showed that humans preferred the taste of a bottle of wine labeled with an expensive price tag over a bottle of the very same wine labeled with a cheaper price tag. In other studies, people thought a painkiller worked better when they paid a higher price for it. But capuchin monkeys aren’t such fools, according to a new study by Yale psychologists that was published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology.

photo Eric KilbyIn a carefully crafted study, capuchin monkeys showed themselves to be immune to the kind of

photo Eric KilbyIn a carefully crafted study, capuchin monkeys showed themselves to be immune to the kind of

status consciousness that often drives human purchasing decisions.

In a series of experiments, the researchers gave the monkeys tokens that they could use to “purchase” various novel foods at different prices. Control studies showed that monkeys understood the differences in price between the foods. But when the researchers tested whether monkeys preferred the taste of the higher-priced goods, they were surprised to find that the monkeys didn’t fall for the bias.

“We know that capuchin monkeys share a number of our own economic biases,” says psychologist Laurie Santos, lead author of the study. “Our previous work has shown that monkeys are loss averse, irrational when it comes to dealing with risk, and even prone to rationalizing their own decisions, just like humans. But this is one of the first domains we’ve tested in which monkeys show more rational behavior than humans do.”

The researchers think that differences in the response of humans and capuchins could stem from the different experiences that monkeys and people have with markets and how they behave. “For humans, higher price tags often signal that other people like a particular good,” Santos says. “Our richer social experiences with markets might be the very thing that leads us – and not monkeys – astray in this case.”

Cullen Hanks was sitting in the dark on a moonless night by the banks of the Guadalupe River, crouched under a glowing sheet lit by a black light. He was taking pictures of moths.

Hanks is part of a team of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) professionals who are using iNaturalist software to further scientific research. iNaturalist.org began as a master’s degree project of Nate Agrin, Jessica Kline, and Ken-ichi Ueda at UC Berkeley’s School of Information in 2008. Their intent was to create software that would allow amateur naturalists to record their sightings and “leave a living record of life on earth.” In 2014 the California Academy of Sciences acquired iNaturalist. Since then, users have logged almost a million animal and plant sightings all over the world.

photo Pat GainesCitizen scientists have used the Texas Nature Tracker to count horned toads, among many other

photo Pat GainesCitizen scientists have used the Texas Nature Tracker to count horned toads, among many other

species under study.

iNaturalist is just one cutting-edge tool that is empowering ordinary people (that is to say, those of us without PhDs) to become citizen scientists. The Great Sunflower Project, for example, asks people across the US to gather information about the pollinators in their yards, schools, and parks. More than 1 million people around the world have helped gather and/or process information from past weather records and night sky happenings via an organization called Galaxy Zoo. Perhaps the best-known citizen-science project is the Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count, now in its 115th year.

Cullen Hanks and others at TPWD are taking the iNaturalist software a step further through the Texas Nature Tracker Projects. The software uses GPS technology to allow users to identify their sighting accurately on a map within 10 meters. This allows scientists to know exactly where the plant or animal was spotted and if the species is on the move. Currently, there are nine statewide Texas Nature Tracker projects that monitor species of concern in the state, including horned toads, hummingbirds, prairie dogs, whooping cranes, mussels, turtles, and even bumblebees.

The Invaders of Texas Program, coordinated by the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center at the University of Texas at Austin, uses a similar platform to engage citizen scientists and researchers to track the spread of invasive species across Texas.

While it might sound out of place for naturalists to bring their cell phones into the wild while trying to connect with nature, Hanks emphasizes that the software is a tool. It’s a tool scientists old and young can use to both connect with nature and do citizen science. And it could be an extremely useful tool to get children outside and back into nature. The software allows users to be in nature, enjoying nature, while using technology to capture and share data that will be used for the benefit of generations to come.

According to a new Duke University study published in November 2014 in Global Environmental Change, citizen-science projects create networks of engaged citizens who are advocating for environmental protection. “Environmental values may be a prominent driver for citizen scientists to seek out volunteer opportunities,” according to the study authors. “These individuals – environmental opinion leaders – have a high concern for wildlife conservation issues and a willingness to expend personal resources in order to gain expertise.”

Scientists are hopeful that citizen-science projects will continue to promote conservation efforts. “What I learned from this study was how important it is to engage larger segments of the population in research,” says Erika Weinthal, one of the authors of the study. “We often assume there’s a dividing line between those who do science and those who are recipients of science, but there’s a lot more room for interaction between the two.”

Citizen-science training programs like the Master Naturalist program, which started in Texas and has spread to 27 other states, are providing a training network for these kinds of projects. Currently, thousands of citizen scientists participate in these programs nationwide, almost 9,000 in Texas alone. These are some of the citizens that researchers like Cullen Hanks of TPWD depend on for their crowd-sourced data. Without them, and iNaturalist, their projects would be years behind.

Research is showing that with current funding reductions for traditional scientific research, citizen scientists will be needed even more in the future. Krithi Karanth, adjunct assistant professor at the Nicholas School and associate conservation scientist at the Wildlife Conservation Society, co-author of the Duke study, agrees. “Getting the public involved in the scientific process goes a long way in building public support for wildlife conservation.”

—Lana Straub

The constant noise of our industrial cities isn’t just an annoyance – it’s also a health risk that contributes to premature deaths, according to a recent assessment from the European Environment Agency.

The EEA reports that one-in-four Europeans (about 125 million people) experience harmful levels of noise pollution, with health risks ranging from sleepless nights to heart disease. The constant din interferes with schoolchildren’s ability to concentrate in class, and also impacts natural ecosystems. Some songbirds, for example, have a harder time attracting mates due to so much human-produced sound.

The number one cause of noise pollution in Europe is road traffic. Railroads, industrial sites, and airports also add to the problem. “Noise pollution is a major environmental health problem in Europe,” the EEA report said, and warned that the “European soundscape” is under threat.

The agency estimated that more than 900,000 cases of hypertension could be traced to noise. All of our human racket causes up to 10,000 premature deaths in Europe annually, the report said. Better urban planning and using different types of car tires could help reduce the effects of noise pollution.

The loudest places in Europe are Luxemborg, Bulgaria, and Belgium, while the quietest are Malta, Iceland, and Germany.

As sea levels rise, lands get submerged, right? Not so in the case of Iceland where the landmass, too, is rising – as much as 1.4 inches per year in some places. Researchers believe the extra uplift could be behind an increase in volcanic activity on the Nordic island.

In new study published in Geophysical Research Letters, a University of Arizona-led team found that as global warming accelerates the melting of the island’s great ice caps, the earth’s crust under it is rebounding. “It’s similar to putting weights on a trampoline. If you take the weights off, the trampoline will bounce right back up to its original flat shape,” Richard Bennett, one of the geologists behind the study, told The Guardian.

The uplift, the scientists say, coincides with the onset of warming that began about 30 years ago. Geologists have long known that as glaciers melt and the weight of ice decreases, the land under it tends to rise. But until now they weren’t sure if the current rebound was related to past deglaciation or modern ice loss. The new study shows that, at least for Iceland, the accelerating uplift is directly related to the thinning of glaciers. “What we’re observing is a climatically induced change in the Earth’s surface,” Bennett says. The researchers say they were quite surprised by how swiftly the rebound in Iceland was occurring.

The danger is that this increased uplift could lead to a further uptick in volcanic activity. Iceland has experienced three eruptions in the last five years, which spewed ash in the air and shut down airline flights. When Eyjafjallajökull blew in 2010, flights across Europe were disrupted for a week.

It’s a story as old as the first human efforts at animal husbandry. Ranchers raise livestock. On occasion, wolves kill livestock. To protect their animals – and their livelihoods – ranchers sometimes kill wolves. This pattern, which has reappeared in recent years in the United States as wolves repopulated western states, has been troubling to conservationists. On some level, however, it has also made sense from the ranchers’ perspective: The fewer wolves there are, the less livestock will be killed, right? Actually, not so much.

New research suggests that livestock depredations actually increase when wolf populations are reduced. The study, led by Robert Wielgus, director of Washington State University’s Large Carnivore Conservation Lab, examined records from 1987 to 2012 in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming to determine death rates of both wolves and livestock. The study found that the chance of livestock depredations increased 4 percent for sheep and 5 to 6 percent for cattle in years following wolf culls (that is, until wolf mortality exceeded 25 percent).

In other words, killing wolves doesn’t actually protect livestock in the long run. In fact, as wolves adapt and increase their reproduction rates in response to population losses, lethal management methods seem to make things worse for ranchers.

Anti-wolf groups have called into question the validity of the results, but Wielgus stands by his findings. “They just want to get rid of wolves,” he told The New York Times. “Livestock lobbyists are pretty much vehemently opposed to my research. But in terms of hard science, it stood the test.”

So what’s the moral of the story? According to Wielgus, lethal control methods may in some situations prevent livestock deaths, but the long-term interests of both ranchers and wolves would be better served by alternative management approaches.

Think that the great outdoors of North America is wilder than the confines of Old Europe? When it comes to the presence of predators, time to think again.

A study published in December by Science concluded that the populations of several large predators are greater in Europe than in the contiguous United States. An estimated 17,000 brown bears inhabit 22 countries in Europe. In comparison, just 1,800 grizzlies live in the US’ Lower 48. There are some 12,000 wolves living in Europe – more than twice the number of wolves that live in the US (not including Alaska). Lynx and wolverine are also making a comeback in Europe. According to the authors of the study, which included the work of 55 biologists across Europe, “Roughly one-third of mainland Europe hosts at least one large carnivore species, with stable or increasing abundance in most cases in twenty-first-century records.”

photo Karin JonssonAccording to a new study, the number of large carvinores in Europes exceeds that in the Continental

photo Karin JonssonAccording to a new study, the number of large carvinores in Europes exceeds that in the Continental

US, even though Europe is much more developed and crowded with humans.

How has this large predator comeback occurred in one of the most industrialized landscapes on Earth? Two changes, the report authors say. First, continuing urbanization has led to an abandonment of marginal farmland, creating more habitat for critters big and small. Second, Europeans have realized that it’s not impossible to coexist with predators. There has been a shift in psychology from hostility to tolerance.

“The European model shows that people and predators can coexist in the same landscapes,” Guillaume Chapron of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences told NationalGeographic.com. “If there is a political will, it is possible to share the landscape with larger predators.”

In short, bears and wolves can find a way to live among humans. Now if only we here in the US can muster up the courage and the patience to live with them.

Years of tiger conservation efforts seem to be finally paying off in India. The tiger population there apparently has grown by more than 30 percent in the past four years, according to a new government census released in January. The latest tally, compiled using 9,735 camera traps set up in forests in 18 states, indicates that the big cat’s numbers rose from 1,706 in 2011 to 2,226 in 2014.

photo Dave MorrisThe Indian government boasts that wild tiger numbers are on the rise. But some conservationists are skeptical of the new figures.

photo Dave MorrisThe Indian government boasts that wild tiger numbers are on the rise. But some conservationists are skeptical of the new figures.

Much of this population rebound is a result of initiatives undertaken by the Indian government – such as setting up a special tiger protection force, creating programs for orphaned cubs, and relocating forest villages – following the embarrassing discovery in 2005 that poachers had killed the entire population of 22 tigers in a preserve in the state of Rajasthan, and a 2007 census that showed that the country’s tiger population had dropped to 1,411.

But while India’s environment minister, Prakash Javadekar, is already making big claims about being able to “give tigers and cubs to any country who wants them,” some conservation experts have expressed doubts about the new figure.

“The degree and extent of this population recovery requires closer examination of detailed data from the survey,” cautions Dr. K. Ullas Karanth, Asia director of the New York-based Wildlife Conservation Society. Though the status of tigers has generally improved, the counting method used in the current census cannot yield “sufficiently refined results to accurately measure changes in tiger numbers at landscape or country-wide scales as is being attempted,” Karanth told reporters. Among other things, he said, the camera trap method can result in inflated numbers because it ignores natural population turnover.

India has some 77,220 square miles of tiger habitat. Well-managed habitats with abundant prey can support between 5,000 to 10,000 tigers in the long-run. “We have a long way to go, but it is doable if we get our act together,” Karanth says.

For northern white rhinos, the march towards extinction seems almost inevitable. In December, Angalifu, a 44-year-old northern white rhino, died at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park in California, leaving only five of his kind on the planet. There are no known northern white rhinos left in the wild. The remaining members of the subspecies include a female at the San Diego Zoo, a female in a zoo in the Czech Republic, and two females and a male at a wildlife conservancy in Kenya, which is involved in a last-ditch effort to breed this extremely rare subspecies.

Since Angalifu was old and not breeding, his passing didn’t bring the subspecies any closer to extinction, said Matthew Lewis, senior program officer for African species conservation at the World Wildlife Fund. “[The subspecies] is in dire shape, and it has been for a long time,” he told National Geographic. “The only chance we’re going to have [to breed] full northern white offspring is [through] artificial insemination.” But so far, this method has proved to be difficult in rhinos. Scientists say there is limited hope of any more of this subspecies being born.

Snowy owls once were rarely seen outside the Arctic, but now the iconic, yellow-eyed raptors are turning up more frequently in the skies of southern Canada and the US Northeast, much to the delight of bird-watchers. Winter sightings of these majestic birds, popularized by the owl Hedwig in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter fantasies, could eclipse last season’s record when the final tally is in, according to preliminary data from the National Audubon Society’s 115th Christmas Bird Count.

photo by Marie Hale, on FlickrTo the delight of bird-watchers, Artic owls have been spotted around the Great Lakes.

photo by Marie Hale, on FlickrTo the delight of bird-watchers, Artic owls have been spotted around the Great Lakes.

In early January, with just a fifth of the counting sessions totaled, there were 303 of the enormous white owls sighted, Geoff LeBaron, the society’s project leader, told Reuters. Last year’s final tally was 1,117 snowy owls, or nearly double the previous high of 563 from the 2011 count. “This is a big flight,” LeBaron said, noting that the birds seem to be congregating in southern Ontario, the Great Lakes, and the US Northeast. “They don’t usually come down this far. When they do, it’s a real treat,” LeBaron said.

Audubon is not expected to release its final tally until June, after it has analyzed data from an estimated 2,400 bird-counting sessions from December 14 to January 5 by volunteers in North, Central, and South America, the Caribbean and some South Pacific islands.

Ornithologists aren’t certain what exactly is causing the southward expansion of the snowy owls’ range. It may be weather related, perhaps connected to shifting temperatures due to climate change. Or it could be due to a bumper crop of owlets in the snowy owl’s Arctic breeding grounds last spring. The owl baby boom was made possible by an unusual abundance of lemmings, a staple of the owls’ diet. “Those owl babies are now adolescents who have to find feeding grounds,” explained Jason Berry of the American Bird Conservancy. “Since snowy owls are very territorial, the youngsters can’t stake out a territory near home in the Arctic because those grounds are already claimed by the adults.”

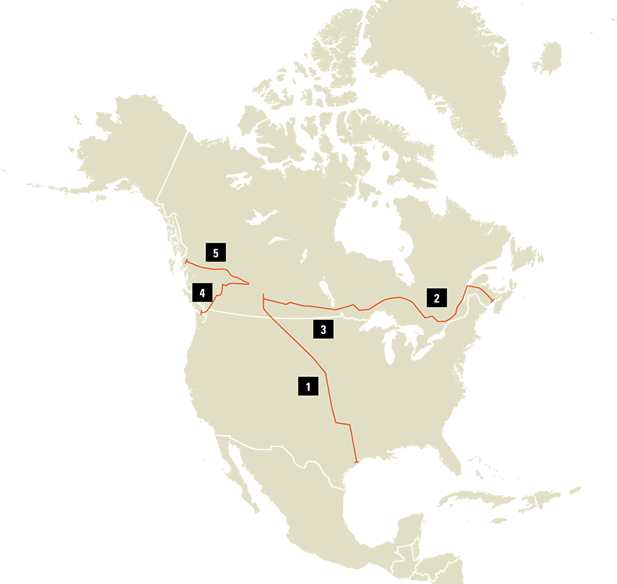

It seems safe to say that the Keystone XL pipeline is the world’s most well-known, and controversial, oil pipeline at the moment. But the United States is already crisscrossed by 61,000 miles of crude oil-carrying pipelines, and Keystone, however infamous, is just one of many contentious pipeline proposals. Pipelines across North America have garnered intense scrutiny for their contributions to climate change, impacts on the local environment, and health and safety concerns. Here are a handful of controversial pipelines in North America.

Pipelines not to scale; visual reference only.

Pipelines not to scale; visual reference only.

We don’t have a paywall because, as a nonprofit publication, our mission is to inform, educate and inspire action to protect our living world. Which is why we rely on readers like you for support. If you believe in the work we do, please consider making a tax-deductible year-end donation to our Green Journalism Fund.

DonateGet four issues of the magazine at the discounted rate of $20.