WINDSWEPT. BLUSTERY. TEMPESTUOUS. These are some of the words that describe my impression of Cape Horn, at the very edge of the world. Throughout history it has been called dismal, barren, bleak. I would add beautiful, austere, singular, biologically vibrant. But atop it all, it’s windy.

In January 2019, I found myself sitting above the noise, peering over the grey, columnar rock that makes the southern headwall of Isla Hornos. I visited the island to conduct research as an ecologist, but I often found myself a bystander to the wind and water. Over the edge of the cliff, the din and disaster of rough seas raged 400 meters below. There was a brief calm, then chaos from a new direction. Violent, gentle, and violent again by turns. The wind almost knocked me off my feet. It felt like standing on the bottom of a river as the current whipped around me — solid ground was there beneath my feet, but the connection was tenuous.

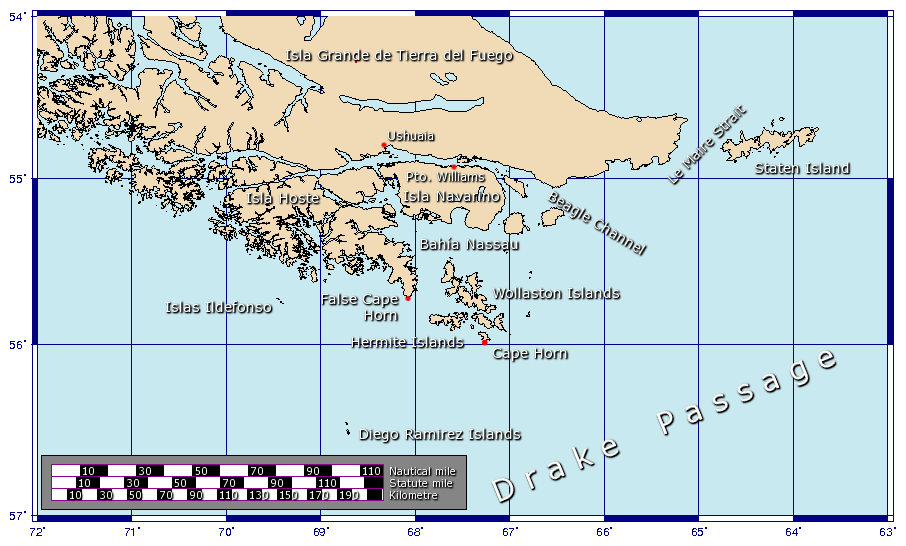

Isla Hornos, the southernmost island in the Cape Horn archipelago and the edge of South America, shoulders up like a castle bulwark from the waters of the Drake Passage, perhaps the deadliest intersection of water, land, and atmosphere on the planet. Southern oceanic storms, unhindered by land, swirl around the entire Earth without losing potency. Approaching Cape Horn, the seafloor abruptly jumps from 4,000 meters to 200 meters in only a few kilometers. The waves stack, some cresting more than 30 meters high. Finally topped by the winds, they crash down onto the cliff bottoms.

Above, the grey chaos of the ocean mirrors the grey, tumultuous underside of the clouds as they race endlessly from west to east. Isla Hornos, which pokes its head into these currents, is barely a speedbump. Rather, it’s like a brave pedestrian cautiously stepping onto a busy freeway. A thousand kilometers to the south, across the Drake, is Antarctica. The only land between here and there is a collection of small islets known as the Diego Ramírez Islands.

A new protected area massively extends the protections of the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve to the Diego Ramírez Islands.

This may be the windiest place on Earth. But it’s a magical place, home of the southernmost trees in the world, an array of seabirds and marine mammals, and awe-inspiring panoramas. It’s a place few people ever see, though some human and nonhuman communities call it home. And it’s a home worth protecting.

As I was wrapping up research at the cape, Chile announced the creation of a new protected area to massively extend the protections of the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve to the Diego Ramírez Islands. These islands host the largest reproductive colony of endangered grey-headed albatross in Chile — the second largest in the world. They also provide a breeding site for a fifth of the world’s population of threatened black-browed albatross — as well a home for more than a quarter of the world’s population of the rapidly declining rockhopper penguin. Migrating whales and other sea life occupy this seascape. Called the Diego Ramírez-Drake Passage Marine Park, the new reserve protects these species, earmarking 144,390 square kilometers of land and ocean that extend almost to the border of the Antarctic.

Cape Horn is a conservation success for Chile and the world, but it’s also the stage for a deep and intriguing historical story. As I stood on the edge of the Earth and looked south, into the grey horizon that now represents one of the world’s largest paired terrestrial/marine conservation areas, I thought about how this latest development is but another chapter in this region’s ecological and human history. The land is changing fast, but so are our views of the land. As an ecologist, I study how landscapes like this serve as a sort of barometer for ecological change. But this landscape can also serve as a barometer for how human perceptions of land have changed, from the original touch of Indigenous peoples to the exploitation of early Europeans, through scientific revelations and natural resource exploitation, to now being one of the most protected places on the planet.

Cape Horn tells a story of a single landscape, remote and mostly barren, that means so many things — a homeland, a science experiment, a tourism resource, a symbol of wilderness.

I LED A RESEARCH team to Isla Hornos with a grant from National Geographic to see what the edge of the Earth could tell us about ecological change. For a little over four weeks the multidisciplinary team combed through the island, carefully counting species and looking for signs of both human and climate-induced change. Botanists bagged specimens for collection on the heath and moors. Fisheries students focused on the streams, looking for signs of invasive salmon. Avian scientists deployed mist nets to trap and identify resident and migratory birds. We set up an audio recorder to document the clicks of bats in the dark. We often didn’t have to go far to find wildlife. Penguins by the tens of thousands chattered, squawked, and paraded across beaches, through tunnels of grass, and past our tents each dawn and dusk.

Cape Horn is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (a distinction held by the Diego Ramírez Islands), Cape Horn marks the northern boundary of the Drake Passage. For decades it was a major milestone on the clipper route, by which sailing ships carried trade around the world. Photo Boris Kasimov.

The waters around the Cape are particularly hazardous due to strong winds and currents and icebergs, making it notorious as a sailors’ graveyard. The albatross-shaped Cape Horn Monument commemorates the lives of thousands of seafarers who perished attempting to sail around the cape. Photo courtesy of Johantheghost/ Wikimedia Commons.

The Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve, which spans nearly 50,000 square kilometers of southern Chile, is one of the last great pristine areas on the planet. It is almost entirely intact — windswept and desolate but largely untouched, partly because of the forbidding weather itself. Most of its human inhabitants live in one of only a couple of small towns. The entire western side of the region, hundreds of islands, glaciers, and mountains, is unpopulated.

This region is not only pristine, it is incredibly singular. Separated from the rest of the continent by the white-capped Andes and the arid Argentinian plains to the north, the plants and animals of Cape Horn have evolved in climatic isolation for millions of years. More recently, only 15,000 years ago, ice sprawling from the mountains dug fjords and excavated cirques that speckle the landscape, trenching out convoluted topography protected from the fury of the westerly winds. Cape Horn itself was probably under ice at the time, but the Diego Ramírez Islands were likely not. Today, temperatures are surprisingly benign. Despite being the last stop before Antarctica, the ocean influence is so strong that snow is infrequent. These islands were potentially important refugia for plant and animal species to repopulate the post-glacial world, resulting in a unique pool of species in a unique and complicated landscape.

From a global perspective, Cape Horn is also special for what it does not have: nonnative species.

In other words, the edge of the continent is like nowhere else — and looks it.

The small stretch of land that is southern Chile, poking into the global south and comprising only 0.1 percent of the world’s land, holds 5 percent of its moss and liverwort species (and 50 percent of those are found only in southwestern South America). A Megallanic beech tree here, at the southern edge of arboreal life, can host 100 species of epiphytes on its trunk, branches, and leaves. As I climbed into the canopy taking measurements, I became intimately familiar with the slick feel of the mossy bark on cold fingers. The animals are equally specialized. Due to the isolation, half of the fish species and a third of the mammals are endemic to this region.

From a global perspective, Cape Horn is also special for what it does not have: nonnative species. Our research on Isla Hornos found no invasive plants or fish; Diego Ramírez matches that, and also has no invasive mammals. This point is significant, as seabirds that nest on the ground are often easy targets for invasive predators like cats, mice, and rats. On the Diego Ramírez Islands available real estate is quite small — the largest island, Isla Bartolomé, is only 93 hectares; the second largest, Isla Gonzalo, is 38 hectares — and they are highly vulnerable to invasion as a result. But it has not happened yet.

“The marine and terrestrial ecosystems of the Cape Horn and Diego Ramírez island groups are one of the few insular systems on the planet that are largely free of direct human impact,” said Ricardo Rozzi, director of the Sub-Antarctic Biocultural Conservation program, coordinated by the Universidad de Magallanes and the University of North Texas. This program has taken a lead in conservation of the region for over a decade, coordinating participants from both hemispheres and recently opening a new research and education facility called the Sub-Antarctic Cape Horn Center in Puerto Williams, the southernmost town in the region and world.

What Chile has done in preserving this landscape is remarkable. The designation of the Diego Ramírez-Drake Passage Marine Park takes it a step further. Aside from protecting habitat for albatross, penguins, whales, and other known wildlife, the cumulative protected area now also reaches beneath the waves, covering the southern continental shelf of the South American continent. Here, a complex of underwater canyons as deep as 4,500 meters and unique environments like the Sars Seamount provide a home to barely-studied endemic species and enormous quantities of sea sponges. The newly protected land-and-seascape has treasures still undiscovered.

The Yaghan peoples — the dominant cultural group in the area when Europeans arrived — even ventured to the far-flung end, the exposed Cape Horn archipelago itself, for hunting. This sea-nomad lifestyle drove a marine economy that provided residents with a wide variety of food and resources, including materials like green obsidian, which was traded over distances of at least 300 km (as the albatross flies).

While the Yaghan saw the landscape as an integral part of their identity, European explorers saw it as an obstacle.

The land was a bounty, with both land- and sea-based resources available around every corner — and in the mishmash of mountains and water, rivers and plains, there are a lot of corners. People were abundant. We are still discovering fish weirs (corrales de pesca) and rock art hidden in caves throughout the archipelago. In lieu of larger political groups, families and kin groups were the highest authority, with local territories, dialects, and customs. In perhaps the strongest possible manifestation of these peoples’ intimate sense of place, every Yaghan child was named after the place they were born, or “the land that welcomes us,” as Lakutaia le Kipa said to Chilean author Patricia Stambuk. One of the last full-blooded Yaghan, Lakutaia le Kipa, who died in 1983, had visited Cape Horn tied to her mother’s back as a child, and knew the landscape intimately. “Lakuta is the name of a bird, and kipa means woman. Each Yaghan carries the name of the place where he or she was born, and my mother brought me into the world in Lakuta Bay.”

While the Yaghan saw the landscape as an integral part of their identity, European explorers saw it as an obstacle. “Nothing could be more dreary than the scene around us,” wrote the eminent explorer Robert Fitzroy as he attempted to navigate the Beagle through this austere landscape. “The lofty, bleak, and barren heights that surround the inhospitable shores … were covered, even low down their sides, with dense clouds, upon which the fierce squalls that assailed us beat, without causing any change: they seemed as immovable as the mountains where they rested…. The weather was that in which, ‘the soul of man dies in him.’”

Why bother exploring, then? The answer, of course, is economics. In the 1500s, as industrious Europe started fanning out across the map, the bulk of the continent stood in the way of lucrative Atlantic-Pacific trade. Several explorers tried and died looking for a way around. Ferdinand Magellan eventually poked his way through, passing through the extravagantly named “Cape of Eleven Thousand Virgins” in 1520 via the jagged strait that now bears his name. But even then, it was still unclear if South America even had an end, or if it was connected to some other southern continent. Sailors blown off course reported seeing “land’s end” in 1525, but the Southern Ocean was then only a rumor, its truth protected by waves as tall as the masts of a ship.

Called the Diego Ramírez-Drake Passage Marine Park, the new reserve protects species like the endangered grey-headed albatross and threatened black-browed albatross, earmarking 144,390 square kilometers of land and ocean that extend almost to the border of the Antarctic. Photo by Omar Barroso, Universidad de Magallanes, Instituto de Ecología y Biodiversidad.

We often didn’t have to go far to find wildlife. Penguins by the tens of thousands chattered, squawked, and paraded across beaches, through tunnels of grass, and past our tents each dawn and dusk. Photo by Omar Barroso.

It didn’t take long for this region to be fully claimed and commercialized by the Dutch East India Company. Disgruntled competitors launched an expedition to find an alternative route, farther south and into the teeth of the wind, but free. Eventually, in January 1616, Willem Schouten and Isaac Le Maire rounded the blasted grey headwall at the tip of the continent. They named this place, which had itself given its name to so many former inhabitants, after Schouten’s hometown of Hoorn, in the Netherlands. The edge of the Earth became Cape Horn.

European trade and exploration came fast and furious after that point, bringing along the attendant missionaries and priests that accompanied expeditions elsewhere in the New World. Ambitious sealers and whalers devastated the local fauna. Invasive rats hitched rides on their boats, landed on some of the islands, and feasted on shorebird eggs. As the region became charted and routine, if still incredibly dangerous, attention became more scientific in nature. Fitzroy, captain of the Beagle, mapped a second route through South America. South of the Strait of Magellan and more protected than rounding the Cape, the Beagle Channel cuts ruler-straight east to west and is lined with snow-capped mountains and glaciers cascading into the ocean. This provided a third route through to the Pacific, strategic and scientific knowledge of the highest value.

Charles Darwin, perhaps the most influential life scientist of the past three centuries, spent considerable time in the area as part of Fitzroy’s second journey. We climbed the same trails as he did farther north, passing treeline high above the Strait on Mount Tarn. While Darwin’s work with the finches and tortoises of the Galapagos is perhaps more famous, the time spent in the global South cemented his ideas of deep time, human evolution, and evolutionary context. Although his original writings display the harsh ethnocentrism of the Europeans of the age, and a tint of that toxic brew which is evolution plus racism, later in life he recanted and spoke more generously of the peoples and landscapes of Cape Horn. But Darwin, like most, never set foot on the cape itself. Weather prohibited any landing.

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the cape rose in literary prominence as people sought passage from East to West. Communication became easier when Thomas Bridges, a missionary of sorts and linguist, labored with the Yaghan and other local groups (the Alacaloof, the Ona, and the Aush) to develop the first dictionary in 1865. But the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 meant the need for the dangerous southward journey was over. And outside of sailing circles and adventure stories the region slumbered back into relative global obscurity.

WHAT THE YAGHAN lived, and Darwin observed, were what my team and I saw on the Cape: a pristine ecosystem where the ocean, land, and air intersect. A landscape with unique genetics shaped by its climatic past, and a legacy rich with human history both congenial and exploitative. But recent years have brought modern pressures to the edge of the Earth, such as a push to open the fjords to foreign-owned salmon-farming operations. Salmon are especially insidious invasive species, should they escape.

The Yaghan, the indigenous inhabitants of the islands south of Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, led a sea-nomad lifestyle and used to venture to the far-flung end, the exposed Cape Horn archipelago itself, for hunting.

Local opposition has met this industry. In 2019, Maria Luisa Muñoz, vice president of the Yaghan community of Bahía Mejillones de Puerto Williams, protested the proposed expansion of nonnative fish farming in the Cape Horn archipelago. “It cannot be that in this place, the gateway to Antarctica, the last Indigenous city on the planet — with three national parks — they are installing salmon farms, an industry not compatible with the Indigenous community, with tourism, with artisanal fishing, with nothing,” she said to the regional news group Radio Polar. So far the resistance has been generally successful.

But strategic resources, be they geographic or economic, hold an allure that is timeless. In a world where humans have added a billion souls in the last dozen years, pristine landscapes are also a resource. Recreational visits to the wildlands of Patagonia have been ramping up by double-digit percentages each year. The Chilean government estimates that for every dollar invested in national parks and reserves in the country, six to ten dollars comes back via tourism.

But this view of the landscape can be similarly extractive, if handled poorly. Rozzi notes ecotourism should provide jobs for locals, promote biodiversity, support cultural conservation principles, and offer an educational experience. But ecotourism can be ecologically destructive. In the Galapagos, where tourism has increased 20-fold in only 35 years, the islands now host more invasive species than native. Many native species have been lost entirely. This runs counter to inclinations to market a region based on its ecological values, and it assumes that preservation will emerge organically from a widespread appreciation of a region’s beauty. “Successful ecotourism requires policies that also consider ecological, social, and cultural attributes of the fragile, unique socio-ecological systems,” Rozzi wrote in a recent report.

The Chilean government is trying to walk this line. It recently promoted “La Ruta de los Parques de la Patagonia” to celebrate the network of national parks and reserves that run the western spine of the Andes. This route starts in the north with Alerce Andino National Park near Puerto Montt and extends south, through Torres del Paine National Park and the newly established Patagonia National Park, all the way to Cabo de Hornos National Park at Cape Horn. Sixty communities and 17 national parks are featured on the 1,700-mile route.

Can the conservation gains deliver on their promises of preservation, despite being a part of the larger world?

But Latin America has challenging economic inertia to overcome. Mass tourism often favors foreign investments, ignoring local options in favor of package deals. A cruise planned, paid for, and sailed out of the United States may leave only a few dollars in the hands of the local community, as opposed to a more local experience at hostels, local museums, and small restaurants. Plus, setting land aside for conservation and ecotourism may limit space for other uses — like homes, storefronts, and local enterprise. This has been a common concern in the region, a landscape that can appear pristine and “peopleless” — a symbol of wilderness — but is in fact home to human occupants as well, including ranchers and fishers.

“We are behind in several things, such as the ability to absorb the tourism boom that is coming,” Jaime Cárcamo, president of the Cape Horn Chamber of Tourism, told Radio Polar last year. “It requires managing large and small tourist operators.” This is on the mind of local conservationists and the organizers behind the new Diego Ramírez-Drake Passage Marine Park. According to Rozzi, the new marine park’s management plan does not restrict local residents from engaging in artisanal fishing (most famously for southern king crab) in any way. “A public private partnership will establish long-term monitoring, education, and sustainable fishing certification for planning, conservation, and sustainable development associated with sustainable tourism and education,” he said.

Can the conservation gains deliver on their promises of preservation, despite being a part of the larger world? Can Cape Horn be both a homeland and a wilderness? Time will tell, but there is reason to be optimistic.

THE LAST LAND on Earth before Antarctica. The intense wind, shaping where one finds this species or that species. The salt spray that favors some shrubs near the shore and others near the peaks. Life is everywhere, a thin coating of woody photosynthetic scrub and waddling penguins burrowed underneath.

This land is a signpost. The next islands to the south are icebound rocks, and then you are in Antarctica. Life has a toehold there as well, of course: Penguins huddle, seals hunt, and two species of vascular plants sprout in protected crannies. Mosses and lichens are not uncommon around the coasts. But Cape Horn and the Diego Ramírez Islands remain the edge of the life-dominated world.

As we tiptoed through Isla Hornos and scaled the cliff edges to the sounds of penguins, I felt a sudden tension between the landscape and myself. Did my research team need to be there? Was the risk of unwitting transportation of invasive species worth this story of the landscape? Does the local community benefit? Was our presence justified to the condors floating above the peak? I don’t have those answers yet, and maybe I never will.

Yet the sea rolls through the Drake Passage with an unbroken fury. And it will continue to roll as it has for millions of years. The landscape is protected, or as protected as it can be given global climate change — temperature increases, wind shifts, and changes in rain and snow will all wreak their special kinds of havoc. But here, for now at least, there is space for movement. An albatross can spread its wings. Life can move and adjust and buy itself some time. And that is worth noting.

We don’t have a paywall because, as a nonprofit publication, our mission is to inform, educate and inspire action to protect our living world. Which is why we rely on readers like you for support. If you believe in the work we do, please consider making a tax-deductible year-end donation to our Green Journalism Fund.

DonateGet four issues of the magazine at the discounted rate of $20.